After a gap of a year, here’s a blog to celebrate the imminent arrival of another season of work at Shrewsbury Castle. Visitors to this website (both of them) may well be wondering why there’s been radio silence for so long. The answer is in part sheer idleness. That accounts for the end of 2019, and then it seemed wise to hang on until the result of a second application for Season 2 at the castle to the Castle Studies Trust became known. That takes us to the end of January 2020 when they said ‘yes’ to a second excavation at Shrewsbury Castle! Fantastic. Thank-you CST. Preparations began.

And then…Covid struck. All bets were off. A July date for the dig seemed madly optimistic. And then, as time went on and the stats got better, a September date was mooted, received with enthusiasm, risks were assessed, and it looks like we have an excavation on our hands.

And then…lightning struck! Taking out my router and, with it (indirectly) my old computer. Only now, with less than a week to go, does it seem safe to stick one’s head over the digital parapet and announce: Season 2 at Shrewsbury Castle, running September 1st to 18th (closed on the 11th for a wedding at the castle (and all sincere best wishes to the determined bride who’s sticking to her plans!); backfilling on the 17th and 18th. And with that, here’s some thoughts on the forthcoming excavation that have recently appeared on the Castle Studies Trust’s own website…

Shrewsbury Castle: a 2020 vision

Last year, the Castle Studies Trust excavation – the first ever to have taken place within the walls of Shrewsbury Castle – produced three headline conclusions. The first was that the work of the young Thomas Telford there for his client, William Pountney M.P. in 1786-90 was, sadly, more destructive of the medieval original than had previously been recognised. The extent of his restoration of the house (now the Soldiers of Shropshire Museum) and the curtain walls has long been known. What wasn’t appreciated was that standing walls of ruined buildings and a 13th-century tower on the motte top were destroyed and reduced to their footings, and the interior of the inner bailey was, it seems, scraped flat, producing a lovely level lawn at the expense of any archaeological deposits overlying the natural gravel of the hilltop. Despite this, infilled negative features (pits and ditches) cut into the gravel survived and were found by our excavation trench. As a result, our second headline conclusion was that the motte was ringed on its landward side by a massive ditch, twelve metres wide: what we know as the inner bailey must, in the early Middle Ages, have been little more than a barbican defending the end of the bridge giving access up the motte.

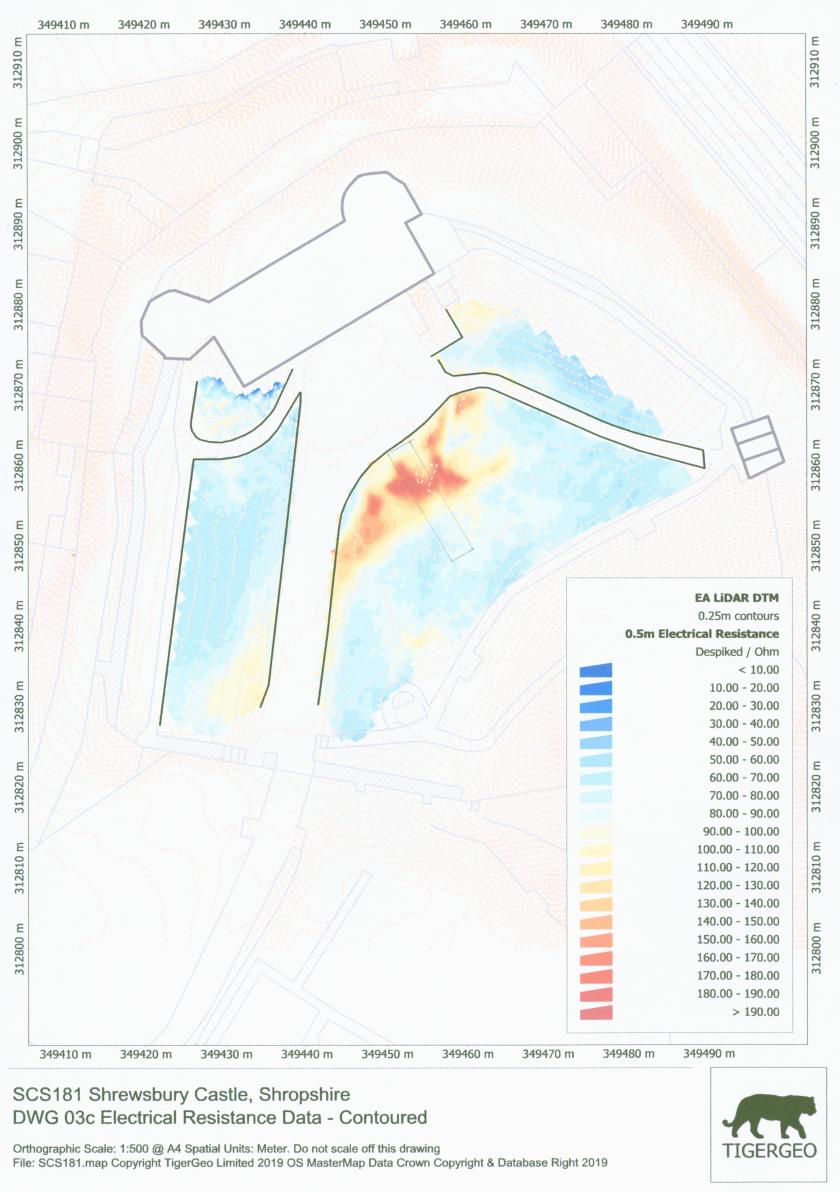

But the extent of Telford’s work raises a question, first put to the archaeological team by Martin Roseveare, our geophysicist: if Telford had the inner bailey levelled flat, where did he put the proceeds, meaning the scraped-up earth and debris? Could the apparently well-preserved medieval ramparts ringing the bailey actually be down to the young Scottish civil engineer, rather than impressed English labour under the whip-hand of William the Conqueror’s henchmen? This is one of the leading questions that a second season of excavation at Shrewsbury Castle hopes to be able to answer, by digging on part of the western rampart known to be already disturbed by former Victorian greenhouses.

There are, however, other at least equally compelling reasons for excavating on this site. The third headline conclusion of the 2019 trench was that there was pre-Conquest activity within the area of the inner bailey. This was demonstrated by a pit, pit 20, containing Stafford-type ware (well known in late pre-Conquest Shrewsbury) and a type of pottery known as TF41a, an import up the Severn from Gloucester, never seen before in Shrewsbury. The question is, what was it doing there?

Shrewsbury is one of those castles listed in Domesday along with the destruction it caused to its ‘host’ shire town. Construction of Shrewsbury Castle took out 51 tax-paying tenements, a quarter or a fifth of the total built-up area, to the economic distress of the remaining inhabitants. Many of the destroyed plots will have lined the strategically important Chester to Hereford road that passes through the outer bailey. However, looming over the road and its plots, and the main gate through the pre-Conquest defences, was the hilltop on which the castle would come to be built. And on it, overlooking the gate, most likely on the Victorian greenhouse site, was the Church of St Michael, a church that became the castle chapel, but was listed in Domesday between the entries for two of the town’s pre-Conquest minsters and was served by two priests later in the Middle Ages, when it was a royal peculiar, exempt from episcopal oversight. This need not necessarily all add up to a pre-Conquest church – but the chances are very strong that it does, and that this church, which, overlooking the town defences, may have had some kind of defensive role, was part of the context of pit 20.

The clues are beginning to point to a high-status site, probably enclosed, with its interior ground level two metres above that of its neighbours, and its own church. For an analogy, one could do worse than look to Wallingford, whose castle in the north-east corner of the Saxon burh had probably taken over and re-fortified a royal site of some kind, possibly housing government functions, perhaps a mint, and a garrison of housecarls. Or one might look to Oxford, where St George’s Tower is now generally thought to be of pre-Conquest date. Shrewsbury seems to be joining the list of Norman town castles established on sites of political, not just tactical, importance.

But archaeology can be frustrating. While we hope that excavation of the Victorian greenhouse site in the west rampart may yield insights into the extent of Thomas Telford’s landscape gardening, the foundations of a pre-Conquest church and further clues to a high-status or even royal site preceding the castle, by 2021 the excavation team may well be singularly well-informed experts on…Victorian greenhouses.